Linux Backdoors:

Part 0 - What are Linux Backdoors?

Purpose

The purpose of this series is to give individuals the background knowledge necessary to become involved in the development of Linux backdoors. I will attempt to provide all necessary information that will be required within the introductory article (part 0).

If there are any questions or issues with material, please feel free to make an issue on github or DM me.

Build

I am using an Ubuntu 16.04.3 LTS (Xenial Xerus) 64-bit PC (AMD64) desktop image VM. Download link can be found here .

I recommend maintaining versions as close to mine as possible. In further articles I will post the version number, kernel version, sha512 hash, as well as other necessities to ensure things will work. I'll also probably make the VM public as soon as I put P1 out.

Assumptions

There are several assumptions that I’ve considered when writing these articles.

- The build environment is the same as mine

- Familiarity with 64 bit environments

- You have some experience with Linux, assembly, and C programming

- You’re willing to dive into source code

- Some understanding of malicious attacks

Layout

This series shall be broken into 5 (possibly 6) chunks that cover various portions of backdoor creation and persistence.

- Part 0 – Introductory reading and basics

- Part 1 – Deep dive into creating a backdoor within a binary (SSH)

- Part 2 – In depth analysis of shared objects and kernel objects

- Part 3 – Shared Object backdoor techniques

- Part 4 – Kernel Object backdoor techniques

- Part 5 – GPU user-land persistence (Tentative)

So...what is Linux?

Linux is a fairly complex series of C, C++, and assembly code that allows for the heavy lifting API interface between user and hardware. This can be distributed into both the Linux (GNU) Operating System and the Linux Kernel. Backdoors can exist in each sector and are often utilized through different mediums. Note that kernel backdoors are almost always going to be more difficult than user backdoors.

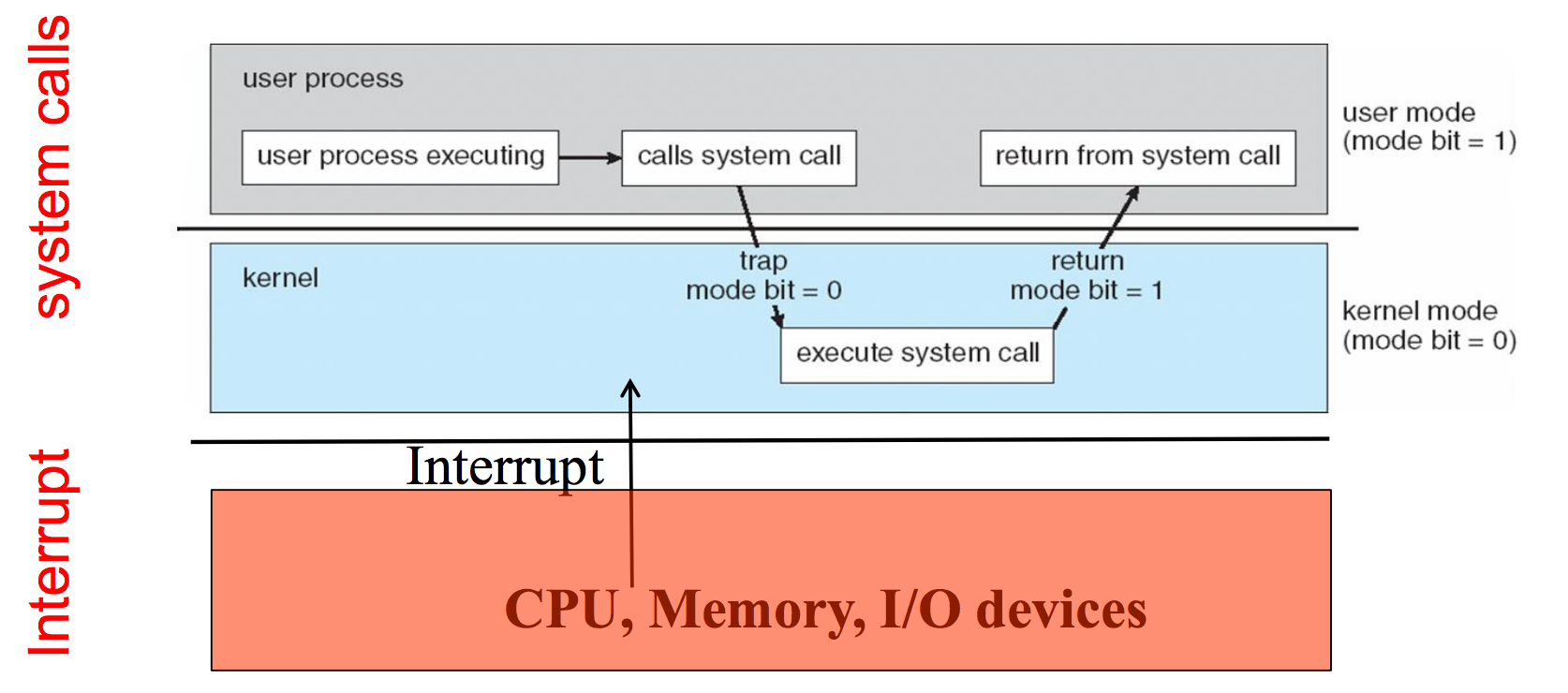

The transfer between user modes and kernel modes happens when a system call is executed, the trap bit is set, and the CS register's 2 bit field has been set to 0 (Note that this is hardware specific, but is relatively the same across most vendors). The values that can be stored within the CS register in linux are 0, most privileges, and 3, least privileges. We tend to classify these sectors as kernel-land and user-space.

Kernel-land

The first thing to start after POST, BIOS, and the MBR is the boot loader(usually GRUB) which then loads the kernel. The kernel generally starts at a ring level of 0, ring levels referring to the level of access and control that something has, and then pivots out of 0 when the O.S. starts. It is imperative to start in ring 0 in order for the kernel to be able to initialize certain values, handle drivers, direct hardware, direct memory, DMA and so on.

Pivoting into kernel-land can be a relatively difficult task. However, this can be done through the use of malicious drivers or kernel object insertion with Loadable Kernel Modules (LKM). LKMs can allow for backdoors to be placed without having to integrate directly into the base kernel source and recompile things. This means that the kernel can essentially be ‘hot patched’, which allows for some malicious use without the need for a reboot. This topic will be covered more in depth with part 2 and 4 of this series.

User-space (user-land)

User space is loaded once the Kernel initializes the O.S. and transfers things over to ring 3, which infers limited access and control. Note this is pretty common and almost mandatory as memory errors and basic use could accidentally cause issues otherwise. User applications and other tools run within user-space. Note that user applications can be defined as a GUI, script, program, etc.

Malicious actors generally pivot into user-space through the use of an exploit or user/password access. As such, it is easiest to lay down persistence within user-land due to the ease of access. User-space persistence generally revolves around deploying backdoors into common binaries or libraries that are used. For instance, a future portion of this series will involve deploying a backdoor into the SSH binary that allows for a certain user to have access without authentication. Shared libraries will also be covered more in part 2 of this series in which I’ll go in depth into how these libraries are created and utilized. After a thorough understanding is gained, I will finally describe the techniques related with examples in practice.

How do they work together?

So we know that only user programs and scripts can be run within user-space, however there are times when user-space needs to access a hardware device or code within the kernel. This can be arranged through an API like interface called system calls.

Image Source: Operating System Concepts - Silberschatz, Galvin, Gange

In the above picture, we can see a user prompting the kernel via a system call. This causes a trap to be issued with the trap bit to be set; another bit is then set to 0 for kernel mode, which allows for execution within the kernel. The kernel takes over and executes the portion in which it is needed then returns execution by setting the trap bit to 1, returning the output from it’s function, and allowing the user-space program to take back control.

This is useful knowledge because it allows us to see how transactions are processed and the separation of powers user-space and kernel-land. It also notes that code cannot be arbitrarily run from within user-space into kernel-land due to how syscalls and other things work. As such, we have to have a special process in order to place a backdoor within the kernel. This process will be covered more in later articles.

Further Reading / References:

http://minnie.tuhs.org/CompArch/Lectures/week05.html

http://www.cs.utsa.edu/~korkmaz/teaching/resources-os-ug/tk-slides/tk01-os-introduction.pdf

http://www.tldp.org/HOWTO/KernelAnalysis-HOWTO-3.html

http://www.thegeekstuff.com/2011/02/linux-boot-process

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Protection_ring

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/User_space

http://www.thegeekstuff.com/2012/07/system-calls-library-functions/

https://w3.cs.jmu.edu/kirkpams/550-f12/papers/linux_rootkit.pdf

https://stackoverflow.com/questions/13185300/where-is-the-mode-bit